Justice Ginsburg on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

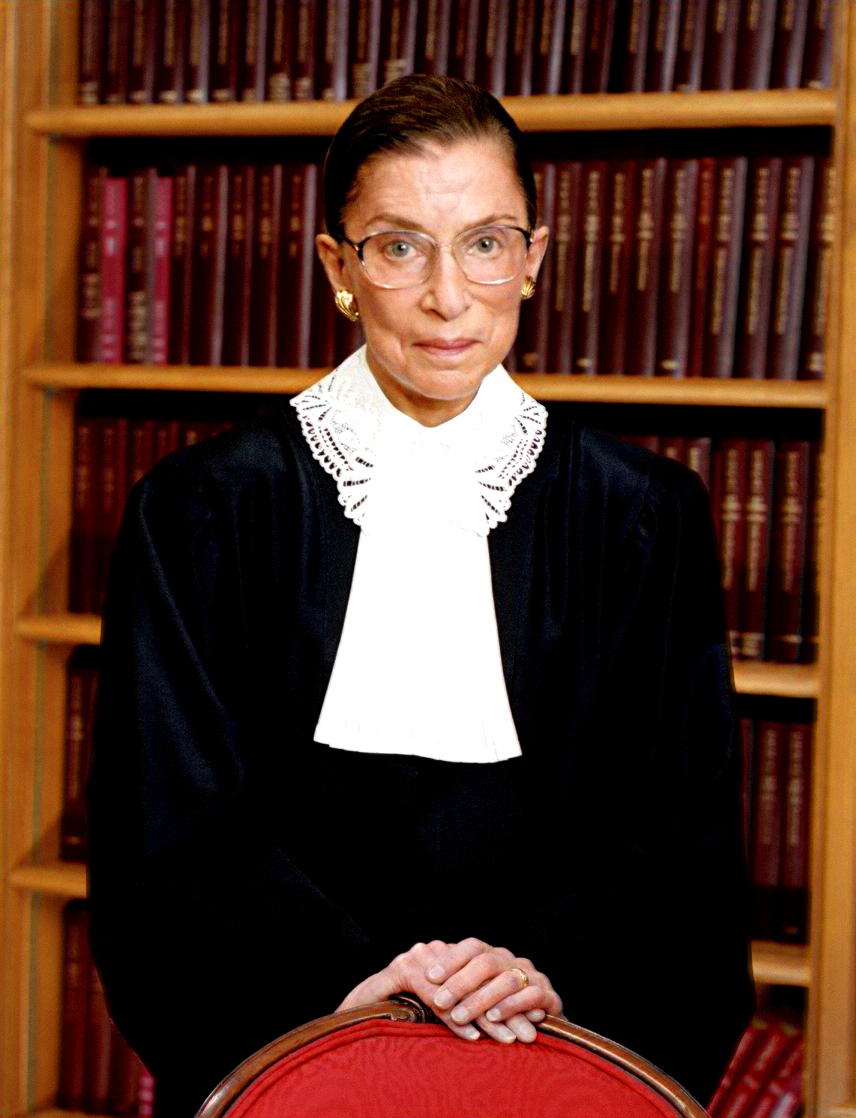

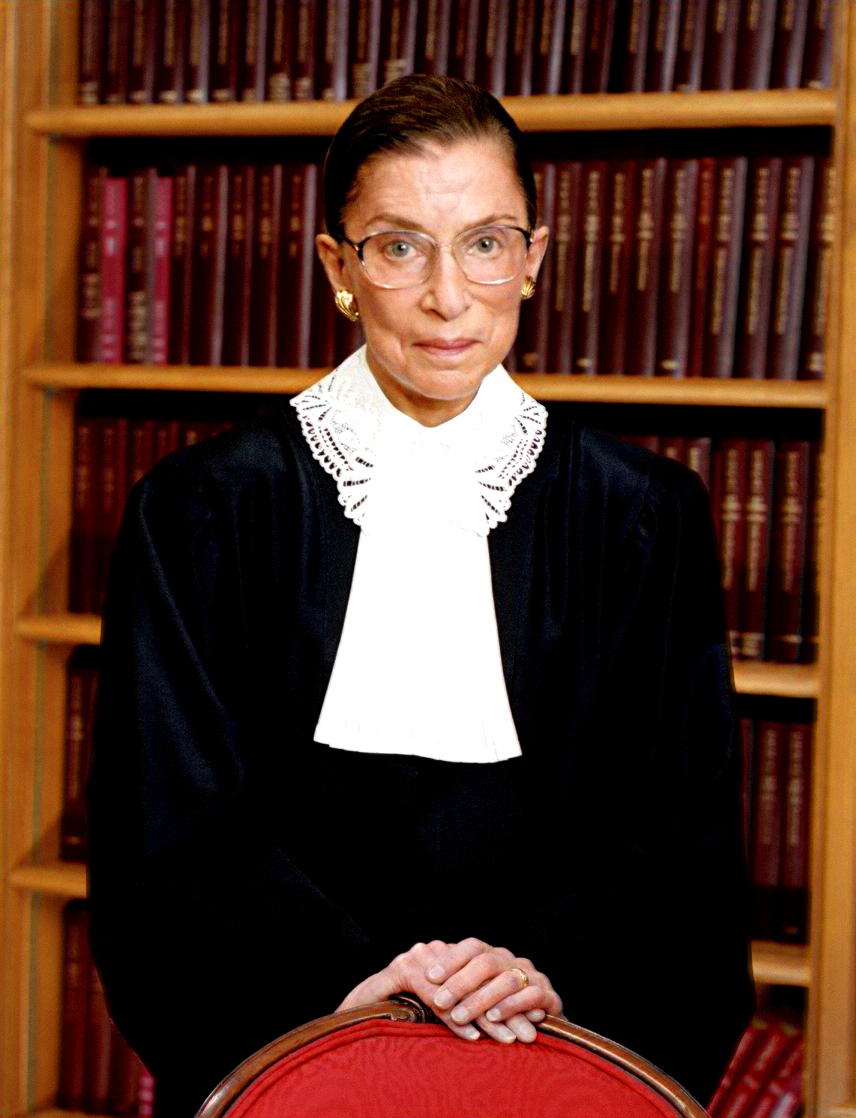

Joan Ruth Bader Ginsburg ( ; ; March 15, 1933September 18, 2020) was an American lawyer and jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1993 until her death in 2020. She was nominated by President

Ruth Bader attended

Ruth Bader attended

Bill Clinton

William Jefferson Clinton ( né Blythe III; born August 19, 1946) is an American politician who served as the 42nd president of the United States from 1993 to 2001. He previously served as governor of Arkansas from 1979 to 1981 and agai ...

to replace retiring justice Byron White

Byron "Whizzer" Raymond White (June 8, 1917 April 15, 2002) was an American professional football player and jurist who served as an associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court from 1962 until his retirement in 1993.

Born and raised in Colo ...

, and at the time was generally viewed as a moderate consensus-builder. She eventually became part of the liberal wing of the Court as the Court shifted to the right over time. Ginsburg was the first Jewish woman and the second woman to serve on the Court, after Sandra Day O'Connor. During her tenure, Ginsburg wrote notable majority opinions, including '' United States v. Virginia''(1996), '' Olmstead v. L.C.''(1999), '' Friends of the Earth, Inc. v. Laidlaw Environmental Services, Inc.''(2000), and '' City of Sherrill v. Oneida Indian Nation of New York''(2005).

Ginsburg was born and grew up in Brooklyn, New York. Her older sister died when she was a baby, and her mother died shortly before Ginsburg graduated from high school. She earned her bachelor's degree at Cornell University

Cornell University is a private statutory land-grant research university based in Ithaca, New York. It is a member of the Ivy League. Founded in 1865 by Ezra Cornell and Andrew Dickson White, Cornell was founded with the intention to tea ...

and married Martin D. Ginsburg, becoming a mother before starting law school at Harvard, where she was one of the few women in her class. Ginsburg transferred to Columbia Law School

Columbia Law School (Columbia Law or CLS) is the law school of Columbia University, a private Ivy League university in New York City. Columbia Law is widely regarded as one of the most prestigious law schools in the world and has always ranked i ...

, where she graduated joint first in her class. During the early 1960s she worked with the Columbia Law School Project on International Procedure, learned Swedish, and co-authored a book with Swedish jurist Anders Bruzelius

Anders Sommar Bruzelius (14 November 1911 – 11 October 2006) was a Swedish jurist, judge and an early collaborator of Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

He earned his jur.kand. (JD) at Stockholm University in 1934, and was a judge on Lund District Court from ...

; her work in Sweden profoundly influenced her thinking on gender equality. She then became a professor at Rutgers Law School

Rutgers Law School is the law school of Rutgers University, with classrooms in Newark and Camden, New Jersey. It is the largest public law school and the 10th largest law school, overall, in the United States. Each class in the three-year J.D. pr ...

and Columbia Law School, teaching civil procedure as one of the few women in her field.

Ginsburg spent much of her legal career as an advocate for gender equality

Gender equality, also known as sexual equality or equality of the sexes, is the state of equal ease of access to resources and opportunities regardless of gender, including economic participation and decision-making; and the state of valuing d ...

and women's rights

Women's rights are the rights and entitlements claimed for women and girls worldwide. They formed the basis for the women's rights movement in the 19th century and the feminist movements during the 20th and 21st centuries. In some countries, ...

, winning many arguments before the Supreme Court. She advocated as a volunteer attorney for the American Civil Liberties Union

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) is a nonprofit organization founded in 1920 "to defend and preserve the individual rights and liberties guaranteed to every person in this country by the Constitution and laws of the United States". T ...

and was a member of its board of directors and one of its general counsel in the 1970s. In 1980, President Jimmy Carter

James Earl Carter Jr. (born October 1, 1924) is an American politician who served as the 39th president of the United States from 1977 to 1981. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, he previously served as th ...

appointed her to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit, where she served until her appointment to the Supreme Court in 1993. Between O'Connor's retirement in 2006 and the appointment of Sonia Sotomayor

Sonia Maria Sotomayor (, ; born June 25, 1954) is an American lawyer and jurist who serves as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. She was nominated by President Barack Obama on May 26, 2009, and has served since ...

in 2009, she was the only female justice on the Supreme Court. During that time, Ginsburg became more forceful with her dissents, notably in '' Ledbetter v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co.''(2007). Ginsburg's dissenting opinion was credited with inspiring the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act

The Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act of 2009 (, ) is a landmark federal statute in the United States that was the first bill signed into law by U.S. President Barack Obama on January 29, 2009. The act amends Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 ...

which was signed into law by President Barack Obama

Barack Hussein Obama II ( ; born August 4, 1961) is an American politician who served as the 44th president of the United States from 2009 to 2017. A member of the Democratic Party, Obama was the first African-American president of the U ...

in 2009, making it easier for employees to win pay discrimination claims. Ginsburg received attention in American popular culture for her passionate dissents in numerous cases, widely seen as reflecting paradigmatically liberal views of the law. She was dubbed "The Notorious R.B.G.", and she later embraced the moniker.

Despite two bouts with cancer and public pleas from liberal law scholars, she decided not to retire in 2013 or 2014 when Democrats could appoint her successor. Ginsburg died at her home in Washington, D.C., on September 18, 2020, at the age of 87, from complications of metastatic

Metastasis is a pathogenic agent's spread from an initial or primary site to a different or secondary site within the host's body; the term is typically used when referring to metastasis by a cancerous tumor. The newly pathological sites, then, ...

pancreatic cancer

Pancreatic cancer arises when cell (biology), cells in the pancreas, a glandular organ behind the stomach, begin to multiply out of control and form a Neoplasm, mass. These cancerous cells have the malignant, ability to invade other parts of t ...

. The vacancy created by her death was filled days later by Amy Coney Barrett

Amy Vivian Coney Barrett (born January 28, 1972) is an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. The fifth woman to serve on the court, she was nominated by President Donald Trump and has served since October 27, 2020. S ...

, a conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization i ...

.

Early life and education

Joan Ruth Bader was born on March 15, 1933, at Beth Moses Hospital in theBrooklyn

Brooklyn () is a borough of New York City, coextensive with Kings County, in the U.S. state of New York. Kings County is the most populous county in the State of New York, and the second-most densely populated county in the United States, be ...

borough of New York City, the second daughter of Celia (née Amster) and Nathan Bader, who lived in the Flatbush neighborhood. Her father was a Jewish emigrant from Odessa

Odesa (also spelled Odessa) is the third most populous city and municipality in Ukraine and a major seaport and transport hub located in the south-west of the country, on the northwestern shore of the Black Sea. The city is also the administrativ ...

, Ukraine, at that time part of the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

, and her mother was born in New York to Jewish parents who came from Kraków

Kraków (), or Cracow, is the second-largest and one of the oldest cities in Poland. Situated on the Vistula River in Lesser Poland Voivodeship, the city dates back to the seventh century. Kraków was the official capital of Poland until 1596 ...

, Poland, at that time part of Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

. The Baders' elder daughter Marylin died of meningitis

Meningitis is acute or chronic inflammation of the protective membranes covering the brain and spinal cord, collectively called the meninges. The most common symptoms are fever, headache, and neck stiffness. Other symptoms include confusion or ...

at age six. Joan, who was 14 months old when Marylin died, was known to the family as "Kiki", a nickname Marylin had given her for being "a kicky baby." When Joan started school, Celia discovered that her daughter's class had several other girls named Joan, so Celia suggested the teacher call her daughter by her second name, Ruth, to avoid confusion. Although not devout, the Bader family belonged to East Midwood Jewish Center, a Conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization i ...

synagogue, where Ruth learned tenets of the Jewish faith and gained familiarity with the Hebrew language

Hebrew (; ; ) is a Northwest Semitic language of the Afroasiatic language family. Historically, it is one of the spoken languages of the Israelites and their longest-surviving descendants, the Jews and Samaritans. It was largely preserved ...

. Ruth was not allowed to have a bat mitzvah ceremony because of Orthodox restrictions on women reading from the Torah, which upset her. Starting as a camper from the age of four, she attended Camp Che-Na-Wah, a Jewish summer program at Lake Balfour near Minerva, New York

Minerva is a town in Essex County, New York, United States. The population was 809 at the 2010 census. The town is named after Minerva, the Roman goddess of wisdom.

The town is located in the southwestern corner of the county. By road, it is n ...

, where she was later a camp counselor until the age of eighteen.

Celia took an active role in her daughter's education, often taking her to the library. Celia had been a good student in her youth, graduating from high school at age 15, yet she could not further her own education because her family instead chose to send her brother to college. Celia wanted her daughter to get more education, which she thought would allow Ruth to become a high school history teacher. Ruth attended James Madison High School, whose law program later dedicated a courtroom in her honor. Celia struggled with cancer throughout Ruth's high school years and died the day before Ruth's high school graduation.

Ruth Bader attended

Ruth Bader attended Cornell University

Cornell University is a private statutory land-grant research university based in Ithaca, New York. It is a member of the Ivy League. Founded in 1865 by Ezra Cornell and Andrew Dickson White, Cornell was founded with the intention to tea ...

in Ithaca, New York

Ithaca is a city in the Finger Lakes region of New York, United States. Situated on the southern shore of Cayuga Lake, Ithaca is the seat of Tompkins County and the largest community in the Ithaca metropolitan statistical area. It is named a ...

, and was a member of Alpha Epsilon Phi

Alpha Epsilon Phi ( or AEPhi) is a sorority and one of the members of the National Panhellenic Conference, an umbrella organization overseeing 26 North American sororities.

It was founded on October 24, 1909, at Barnard College in Morningside ...

. While at Cornell, she met Martin D. Ginsburg at age 17. She graduated from Cornell with a Bachelor of Arts degree in government on June 23, 1954. While at Cornell, Bader studied under Russian-American novelist Vladimir Nabokov

Vladimir Vladimirovich Nabokov (russian: link=no, Владимир Владимирович Набоков ; 2 July 1977), also known by the pen name Vladimir Sirin (), was a Russian-American novelist, poet, translator, and entomologist. Bo ...

, and she later identified Nabokov as a major influence on her development as a writer. She was a member of Phi Beta Kappa

The Phi Beta Kappa Society () is the oldest academic honor society in the United States, and the most prestigious, due in part to its long history and academic selectivity. Phi Beta Kappa aims to promote and advocate excellence in the liberal a ...

and the highest-ranking female student in her graduating class. Bader married Ginsburg a month after her graduation from Cornell. The couple moved to Fort Sill, Oklahoma

Fort Sill is a United States Army post north of Lawton, Oklahoma, about 85 miles (136.8 km) southwest of Oklahoma City. It covers almost .

The fort was first built during the Indian Wars. It is designated as a National Historic Landmark ...

, where Martin Ginsburg was stationed as a Reserve Officers' Training Corps

The Reserve Officers' Training Corps (ROTC ( or )) is a group of college- and university-based officer-training programs for training commissioned officers of the United States Armed Forces.

Overview

While ROTC graduate officers serve in all ...

officer in the United States Army Reserve

The United States Army Reserve (USAR) is a Military reserve force, reserve force of the United States Army. Together, the Army Reserve and the Army National Guard constitute the Army element of the reserve components of the United States Armed F ...

after his call-up to active duty. At age 21, Ruth Bader Ginsburg worked for the Social Security Administration

The United States Social Security Administration (SSA) is an Independent agencies of the United States government, independent agency of the Federal government of the United States, U.S. federal government that administers Social Security (United ...

office in Oklahoma, where she was demoted after becoming pregnant with her first child. She gave birth to a daughter in 1955.

In the fall of 1956, Ruth Bader Ginsburg enrolled at Harvard Law School

Harvard Law School (Harvard Law or HLS) is the law school of Harvard University, a private research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1817, it is the oldest continuously operating law school in the United States.

Each class ...

, where she was one of only 9 women in a class of about 500 men. The dean of Harvard Law, Erwin Griswold

Erwin Nathaniel Griswold (; July 14, 1904 – November 19, 1994) was an American appellate attorney who argued many cases before the U.S. Supreme Court. Griswold served as Solicitor General of the United States (1967–1973) under Presidents Lynd ...

, reportedly invited all the female law students to dinner at his family home and asked the female law students, including Ginsburg, "Why are you at Harvard Law School, taking the place of a man?" When her husband took a job in New York City, that same dean denied Ginsburg's request to complete her third year towards a Harvard law degree at Columbia Law School

Columbia Law School (Columbia Law or CLS) is the law school of Columbia University, a private Ivy League university in New York City. Columbia Law is widely regarded as one of the most prestigious law schools in the world and has always ranked i ...

, so Ginsburg transferred to Columbia and became the first woman to be on two major law review

A law review or law journal is a scholarly journal or publication that focuses on legal issues. A law review is a type of legal periodical. Law reviews are a source of research, imbedded with analyzed and referenced legal topics; they also pro ...

s: the ''Harvard Law Review

The ''Harvard Law Review'' is a law review published by an independent student group at Harvard Law School. According to the ''Journal Citation Reports'', the ''Harvard Law Review''s 2015 impact factor of 4.979 placed the journal first out of 143 ...

'' and ''Columbia Law Review

The ''Columbia Law Review'' is a law review edited and published by students at Columbia Law School. The journal publishes scholarly articles, essays, and student notes.

It was established in 1901 by Joseph E. Corrigan and John M. Woolsey, who se ...

''. In 1959, she earned her law degree at Columbia and tied for first in her class. Toobin, Jeffrey (2007). '' The Nine: Inside the Secret World of the Supreme Court'', New York, Doubleday, p. 82.

Early career

At the start of her legal career, Ginsburg encountered difficulty in finding employment. In 1960, Supreme Court JusticeFelix Frankfurter

Felix Frankfurter (November 15, 1882 – February 22, 1965) was an Austrian-American jurist who served as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1939 until 1962, during which period he was a noted advocate of judicia ...

rejected Ginsburg for a clerkship because of her gender. He did so despite a strong recommendation from Albert Martin Sacks

Albert Martin Sacks (August 15, 1920 – March 22, 1991) was an American lawyer and former Dean of Harvard Law School.

Born in New York City to Jewish immigrants from Russia, he attended City College of New York graduating in 1940. After servin ...

, who was a professor and later dean

Dean may refer to:

People

* Dean (given name)

* Dean (surname), a surname of Anglo-Saxon English origin

* Dean (South Korean singer), a stage name for singer Kwon Hyuk

* Dean Delannoit, a Belgian singer most known by the mononym Dean

Titles

* ...

of Harvard Law School. Columbia law professor Gerald Gunther also pushed for Judge Edmund L. Palmieri of the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York to hire Ginsburg as a law clerk

A law clerk or a judicial clerk is a person, generally someone who provides direct counsel and assistance to a lawyer or judge by researching issues and drafting legal opinions for cases before the court. Judicial clerks often play significant ...

, threatening to never recommend another Columbia student to Palmieri if he did not give Ginsburg the opportunity and guaranteeing to provide the judge with a replacement clerk should Ginsburg not succeed. Later that year, Ginsburg began her clerkship for Judge Palmieri, and she held the position for two years.

Academia

From 1961 to 1963, Ginsburg was a research associate and then an associate director of the Columbia Law School Project on International Procedure, working alongside directorHans Smit

Hans-Peter Van Sprew Smit (born June 29, 1958) is an Indonesian-born Filipino football coach. He was assistant coach of the Philippine national football team which participated at the 1996 Tiger Cup.

He is the current head coach of the DLSU Lady ...

; she learned Swedish

Swedish or ' may refer to:

Anything from or related to Sweden, a country in Northern Europe. Or, specifically:

* Swedish language, a North Germanic language spoken primarily in Sweden and Finland

** Swedish alphabet, the official alphabet used by ...

to co-author a book with Anders Bruzelius

Anders Sommar Bruzelius (14 November 1911 – 11 October 2006) was a Swedish jurist, judge and an early collaborator of Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

He earned his jur.kand. (JD) at Stockholm University in 1934, and was a judge on Lund District Court from ...

on civil procedure in Sweden. Ginsburg conducted extensive research for her book at Lund University

, motto = Ad utrumque

, mottoeng = Prepared for both

, established =

, type = Public research university

, budget = SEK 9 billion Bruzelius' daughter, Norwegian supreme court justice and president of the

In 1972, Ginsburg co-founded the Women's Rights Project at the

In 1972, Ginsburg co-founded the Women's Rights Project at the

"Redefining Fair With a Simple Careful Assault—Step-by-Step Strategy Produced Strides for Equal Protection"

''

At the time, Ginsburg was a fellow at Stanford University where she was working on a written account of her work in litigation and advocacy for equal rights. Her husband was a visiting professor at

At the time, Ginsburg was a fellow at Stanford University where she was working on a written account of her work in litigation and advocacy for equal rights. Her husband was a visiting professor at

President

President  During her testimony before the

During her testimony before the

With the retirement of Justice

With the retirement of Justice

Ginsburg dissented in the Court's decision on '' Ledbetter v. Goodyear'', , in which plaintiff

Ginsburg dissented in the Court's decision on '' Ledbetter v. Goodyear'', , in which plaintiff

Exclusive: Supreme Court's Ginsburg vows to resist pressure to retire

,

At his request, Ginsburg administered the

At his request, Ginsburg administered the  During three interviews in July 2016, Ginsburg criticized presumptive Republican presidential nominee

During three interviews in July 2016, Ginsburg criticized presumptive Republican presidential nominee

A few days after Ruth Bader graduated from Cornell, she married Martin D. Ginsburg, who later became an internationally prominent tax attorney practicing at Weil, Gotshal & Manges. Upon Ruth Bader Ginsburg's accession to the D.C. Circuit, the couple moved from New York City to Washington, D.C., where Martin became a professor of law at

A few days after Ruth Bader graduated from Cornell, she married Martin D. Ginsburg, who later became an internationally prominent tax attorney practicing at Weil, Gotshal & Manges. Upon Ruth Bader Ginsburg's accession to the D.C. Circuit, the couple moved from New York City to Washington, D.C., where Martin became a professor of law at

Ginsburg died from complications of pancreatic cancer on September 18, 2020, at age 87. She died on the eve of

Ginsburg died from complications of pancreatic cancer on September 18, 2020, at age 87. She died on the eve of

In 2002, Ginsburg was inducted into the

In 2002, Ginsburg was inducted into the

Norwegian Association for Women's Rights

The Norwegian Association for Women's Rights ( no, italic=no, Norsk Kvinnesaksforening; NKF) is Norway's oldest and preeminent women's and girls' rights organization and works "to promote gender equality and all women's and girls' human rights thr ...

, Karin M. Bruzelius

Karin Maria Bruzelius (born 19 February 1941) is a Swedish-born Norwegian supreme court justice and former president of the Norwegian Association for Women's Rights. In 1989, she became the first woman to be appointed Permanent Secretary of a gove ...

, herself a law student when Ginsburg worked with her father, said that "by getting close to my family, Ruth realized that one could live in a completely different way, that women could have a different lifestyle and legal position than what they had in the United States."

Ginsburg's first position as a professor was at Rutgers Law School

Rutgers Law School is the law school of Rutgers University, with classrooms in Newark and Camden, New Jersey. It is the largest public law school and the 10th largest law school, overall, in the United States. Each class in the three-year J.D. pr ...

in 1963. She was paid less than her male colleagues because, she was told, "your husband has a very good job." At the time Ginsburg entered academia, she was one of fewer than twenty female law professors in the United States. She was a professor of law at Rutgers from 1963 to 1972, teaching mainly civil procedure

Civil procedure is the body of law that sets out the rules and standards that courts follow when adjudicating civil lawsuits (as opposed to procedures in criminal law matters). These rules govern how a lawsuit or case may be commenced; what ki ...

and receiving tenure in 1969.

In 1970, she co-founded the ''Women's Rights Law Reporter

The ''Women's Rights Law Reporter'' is a journal of legal scholarship published by an independent student group at Rutgers School of Law—Newark. The journal was founded in 1970 by Rutgers law students working with Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Profess ...

'', the first law journal in the U.S. to focus exclusively on women's rights. From 1972 to 1980, she taught at Columbia Law School, where she became the first tenured woman and co-authored the first law school casebook

A casebook is a type of textbook used primarily by students in law schools.Wayne L. Anderson and Marilyn J. Headrick, The Legal Profession: Is it for you?' (Cincinnati: Thomson Executive Press, 1996), 83. Rather than simply laying out the legal do ...

on sex discrimination

Sexism is prejudice or discrimination based on one's sex or gender. Sexism can affect anyone, but it primarily affects women and girls.There is a clear and broad consensus among academic scholars in multiple fields that sexism refers primaril ...

. She also spent a year as a fellow of the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences

The Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences (CASBS) is an interdisciplinary research lab at Stanford University that offers a residential postdoctoral fellowship program for scientists and scholars studying "the five core social a ...

at Stanford University

Stanford University, officially Leland Stanford Junior University, is a private research university in Stanford, California. The campus occupies , among the largest in the United States, and enrolls over 17,000 students. Stanford is consider ...

from 1977 to 1978.

Litigation and advocacy

In 1972, Ginsburg co-founded the Women's Rights Project at the

In 1972, Ginsburg co-founded the Women's Rights Project at the American Civil Liberties Union

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) is a nonprofit organization founded in 1920 "to defend and preserve the individual rights and liberties guaranteed to every person in this country by the Constitution and laws of the United States". T ...

(ACLU), and in 1973, she became the Project's general counsel. The Women's Rights Project and related ACLU projects participated in more than 300 gender discrimination cases by 1974. As the director of the ACLU's Women's Rights Project, she argued six gender discrimination cases before the Supreme Court between 1973 and 1976, winning five. Rather than asking the Court to end all gender discrimination at once, Ginsburg charted a strategic course, taking aim at specific discriminatory statutes and building on each successive victory. She chose plaintiffs carefully, at times picking male plaintiffs to demonstrate that gender discrimination was harmful to both men and women. The laws Ginsburg targeted included those that on the surface appeared beneficial to women, but in fact reinforced the notion that women needed to be dependent on men. Her strategic advocacy extended to word choice, favoring the use of "gender" instead of "sex", after her secretary suggested the word "sex" would serve as a distraction to judges. She attained a reputation as a skilled oral advocate, and her work led directly to the end of gender discrimination in many areas of the law.

Ginsburg volunteered to write the brief for ''Reed v. Reed

''Reed v. Reed'', 404 U.S. 71 (1971), was a landmark decision of the Supreme Court of the United States holding that the administrators of estates cannot be named in a way that discriminates between sexes. In ''Reed v. Reed'' the Supreme Court rule ...

'', , in which the Supreme Court extended the protections of the Equal Protection Clause

The Equal Protection Clause is part of the first section of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. The clause, which took effect in 1868, provides "''nor shall any State ... deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal ...

of the Fourteenth Amendment to women. In 1972, she argued before the 10th Circuit in ''Moritz v. Commissioner

''Charles E. Moritz v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue'', 469 F.2d 466 (1972), was a case before the United States Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit in which the Court held that discrimination on the basis of sex constitutes a violation of ...

'' on behalf of a man who had been denied a caregiver deduction because of his gender. As ''amicus'' she argued in '' Frontiero v. Richardson'', , which challenged a statute making it more difficult for a female service member (Frontiero) to claim an increased housing allowance for her husband than for a male service member seeking the same allowance for his wife. Ginsburg argued that the statute treated women as inferior, and the Supreme Court ruled 8–1 in Frontiero's favor. The court again ruled in Ginsburg's favor in '' Weinberger v. Wiesenfeld'', , where Ginsburg represented a widower denied survivor benefits under Social Security, which permitted widows but not widowers to collect special benefits while caring for minor children. She argued that the statute discriminated against male survivors of workers by denying them the same protection as their female counterparts.

In 1973, the same year ''Roe v. Wade

''Roe v. Wade'', 410 U.S. 113 (1973),. was a landmark decision of the U.S. Supreme Court in which the Court ruled that the Constitution of the United States conferred the right to have an abortion. The decision struck down many federal and st ...

'' was decided, Ginsburg filed a federal case to challenge involuntary sterilization

Compulsory sterilization, also known as forced or coerced sterilization, is a government-mandated program to involuntarily sterilize a specific group of people. Sterilization removes a person's capacity to reproduce, and is usually done throug ...

, suing members of the Eugenics Board of North Carolina on behalf of Nial Ruth Cox, a mother who had been coercively sterilized under North Carolina's Sterilization of Persons Mentally Defective program on penalty of her family losing welfare benefits. During a 2009 interview with Emily Bazelon

Emily Bazelon (born March 4, 1971) is an American journalist. She is a staff writer for ''The New York Times Magazine,'' a senior research fellow at Yale Law School, and co-host of the ''Slate'' podcast ''Political Gabfest''. She is a former sen ...

of ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'', Ginsburg stated: "I had thought that at the time ''Roe'' was decided, there was concern about population growth and particularly growth in populations that we don't want to have too many of." Bazelon conducted a follow-up interview with Ginsburg in 2012 at a joint appearance at Yale University

Yale University is a private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. Established in 1701 as the Collegiate School, it is the third-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and among the most prestigious in the wo ...

, where Ginsburg claimed her 2009 quote was vastly misinterpreted and clarified her stance.

Ginsburg filed an amicus brief

An ''amicus curiae'' (; ) is an individual or organization who is not a party to a legal case, but who is permitted to assist a court by offering information, expertise, or insight that has a bearing on the issues in the case. The decision on ...

and sat with counsel at oral argument for ''Craig v. Boren

''Craig v. Boren'', 429 U.S. 190 (1976), was a List of landmark court decisions in the United States, landmark decision of the US Supreme Court ruling that statutory or administrative sex classifications were subject to intermediate scrutiny under ...

'', , which challenged an Oklahoma statute that set different minimum drinking ages for men and women. For the first time, the court imposed what is known as intermediate scrutiny

Intermediate scrutiny, in U.S. constitutional law, is the second level of deciding issues using judicial review. The other levels are typically referred to as rational basis review (least rigorous) and strict scrutiny (most rigorous).

In order t ...

on laws discriminating based on gender, a heightened standard of Constitutional review. Her last case as an attorney before the Supreme Court was ''Duren v. Missouri

''Duren v. Missouri'', 439 U.S. 357 (1979), was a United States Supreme Court case related to the Sixth Amendment. It challenged Missouri's law allowing gender-based exemption from jury service.

Ruth Bader Ginsburg, who later became a Supreme Co ...

'', , which challenged the validity of voluntary jury duty

Jury duty or jury service is service as a juror in a legal proceeding.

Juror selection process

The prosecutor and defense can dismiss potential jurors for various reasons, which can vary from one state to another, and they can have a specific ...

for women, on the ground that participation in jury duty was a citizen's vital governmental service and therefore should not be optional for women. At the end of Ginsburg's oral argument, then-Associate Justice William Rehnquist

William Hubbs Rehnquist ( ; October 1, 1924 – September 3, 2005) was an American attorney and jurist who served on the U.S. Supreme Court for 33 years, first as an associate justice from 1972 to 1986 and then as the 16th chief justice from ...

asked Ginsburg, "You won't settle for putting Susan B. Anthony

Susan B. Anthony (born Susan Anthony; February 15, 1820 – March 13, 1906) was an American social reformer and women's rights activist who played a pivotal role in the women's suffrage movement. Born into a Quaker family committed to s ...

on the new dollar, then?"Von Drehle, David (July 19, 1993)"Redefining Fair With a Simple Careful Assault—Step-by-Step Strategy Produced Strides for Equal Protection"

''

The Washington Post

''The Washington Post'' (also known as the ''Post'' and, informally, ''WaPo'') is an American daily newspaper published in Washington, D.C. It is the most widely circulated newspaper within the Washington metropolitan area and has a large nati ...

''. Retrieved August 24, 2009. Ginsburg said she considered responding, "We won't settle for tokens," but instead opted not to answer the question.

Legal scholars and advocates credit Ginsburg's body of work with making significant legal advances for women under the Equal Protection Clause of the Constitution. Taken together, Ginsburg's legal victories discouraged legislatures from treating women and men differently under the law. She continued to work on the ACLU's Women's Rights Project until her appointment to the Federal Bench in 1980. Later, colleague Antonin Scalia

Antonin Gregory Scalia (; March 11, 1936 – February 13, 2016) was an American jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1986 until his death in 2016. He was described as the intellectu ...

praised Ginsburg's skills as an advocate. "She became the leading (and very successful) litigator on behalf of women's rights—the Thurgood Marshall

Thurgood Marshall (July 2, 1908 – January 24, 1993) was an American civil rights lawyer and jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1967 until 1991. He was the Supreme Court's first African-A ...

of that cause, so to speak." This was a comparison that had first been made by former solicitor general Erwin Griswold

Erwin Nathaniel Griswold (; July 14, 1904 – November 19, 1994) was an American appellate attorney who argued many cases before the U.S. Supreme Court. Griswold served as Solicitor General of the United States (1967–1973) under Presidents Lynd ...

who was also her former professor and dean at Harvard Law School, in a speech given in 1985.

U.S. Court of Appeals

In light of the mounting backlog in the federal judiciary, Congress passed the Omnibus Judgeship Act of 1978 increasing the number of federal judges by 117 in district courts and another 35 to be added to the circuit courts. The law placed an emphasis on ensuring that the judges included women and minority groups, a matter that was important to PresidentJimmy Carter

James Earl Carter Jr. (born October 1, 1924) is an American politician who served as the 39th president of the United States from 1977 to 1981. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, he previously served as th ...

who had been elected two years before. The bill also required that the nomination process consider the character and experience of the candidates. Ginsburg was considering a change in career as soon as Carter was elected. She was interviewed by the Department of Justice

A justice ministry, ministry of justice, or department of justice is a ministry or other government agency in charge of the administration of justice. The ministry or department is often headed by a minister of justice (minister for justice in a v ...

to become Solicitor General, the position she most desired, but knew that she and the African-American candidate who was interviewed the same day had little chance of being appointed by Attorney General Griffin Bell

Griffin Boyette Bell (October 31, 1918 – January 5, 2009) was the 72nd Attorney General of the United States, having served under President Jimmy Carter. Previously, he was a U.S. circuit judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the Fift ...

.

At the time, Ginsburg was a fellow at Stanford University where she was working on a written account of her work in litigation and advocacy for equal rights. Her husband was a visiting professor at

At the time, Ginsburg was a fellow at Stanford University where she was working on a written account of her work in litigation and advocacy for equal rights. Her husband was a visiting professor at Stanford Law School

Stanford Law School (Stanford Law or SLS) is the law school of Stanford University, a private research university near Palo Alto, California. Established in 1893, it is regarded as one of the most prestigious law schools in the world. Stanford La ...

and was ready to leave his firm, Weil, Gotshal & Manges

Weil, Gotshal & Manges LLP is an American international law firm with approximately 1,100 attorneys, headquartered in New York City. With a gross annual revenue in excess of $1.8 billion, it is among the world's largest law firms according to ' ...

, for a tenured position. He was at the same time working hard to promote a possible judgeship for his wife. In January 1979, she filled out the questionnaire for possible nominees to the U.S. Court of Appeals

The United States courts of appeals are the intermediate appellate courts of the United States federal judiciary. The courts of appeals are divided into 11 numbered circuits that cover geographic areas of the United States and hear appeals fr ...

for the Second Circuit, and another for the District of Columbia Circuit. Ginsburg was nominated by President Carter on April 14, 1980, to a seat on the DC Circuit vacated by Judge Harold Leventhal

Harold Leventhal (May 24, 1919 – October 4, 2005) was an American music manager. He died in 2005 at the age of 86. Leventhal's career began as a song plugger for Irving Berlin and then Benny Goodman. While working for Goodman, he connected ...

upon his death. She was confirmed by the United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and pow ...

on June 18, 1980, and received her commission later that day.

During her time as a judge on the DC Circuit, Ginsburg often found consensus with her colleagues including conservatives Robert H. Bork

Robert Heron Bork (March 1, 1927 – December 19, 2012) was an American jurist who served as the solicitor general of the United States from 1973 to 1977. A professor at Yale Law School by occupation, he later served as a judge on the U.S. Cour ...

and Antonin Scalia

Antonin Gregory Scalia (; March 11, 1936 – February 13, 2016) was an American jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1986 until his death in 2016. He was described as the intellectu ...

. Her time on the court earned her a reputation as a "cautious jurist" and a moderate. Her service ended on August 9, 1993, due to her elevation to the United States Supreme Court, and she was replaced by Judge David S. Tatel

David S. Tatel (born March 16, 1942) is an American lawyer who serves as a Senior United States circuit judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit.

Education and career

Tatel received his Bachelor of Arts ...

.

Supreme Court

Nomination and confirmation

President

President Bill Clinton

William Jefferson Clinton ( né Blythe III; born August 19, 1946) is an American politician who served as the 42nd president of the United States from 1993 to 2001. He previously served as governor of Arkansas from 1979 to 1981 and agai ...

nominated Ginsburg as an associate justice of the Supreme Court on June 22, 1993, to fill the seat vacated by retiring justice Byron White

Byron "Whizzer" Raymond White (June 8, 1917 April 15, 2002) was an American professional football player and jurist who served as an associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court from 1962 until his retirement in 1993.

Born and raised in Colo ...

. She was recommended to Clinton by then–U.S. attorney general

In most common law jurisdictions, the attorney general or attorney-general (sometimes abbreviated AG or Atty.-Gen) is the main legal advisor to the government. The plural is attorneys general.

In some jurisdictions, attorneys general also have exec ...

Janet Reno

Janet Wood Reno (July 21, 1938 – November 7, 2016) was an American lawyer who served as the 78th United States attorney general. She held the position from 1993 to 2001, making her the second-longest serving attorney general, behind only Wi ...

, after a suggestion by Utah Republican senator Orrin Hatch

Orrin Grant Hatch (March 22, 1934 – April 23, 2022) was an American attorney and politician who served as a United States senator from Utah from 1977 to 2019. Hatch's 42-year Senate tenure made him the longest-serving Republican U.S. senator ...

. At the time of her nomination, Ginsburg was viewed as having been a moderate and a consensus-builder in her time on the appeals court. Clinton was reportedly looking to increase the Court's diversity, which Ginsburg did as the first Jewish justice since the 1969 resignation of Justice Abe Fortas

Abraham Fortas (June 19, 1910 – April 5, 1982) was an American lawyer and jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1965 to 1969. Born and raised in Memphis, Tennessee, Fortas graduated from Rhod ...

. She was the second female and the first Jewish female justice of the Supreme Court. She eventually became the longest-serving Jewish justice. The American Bar Association

The American Bar Association (ABA) is a voluntary bar association of lawyers and law students, which is not specific to any jurisdiction in the United States. Founded in 1878, the ABA's most important stated activities are the setting of acad ...

's Standing Committee on the Federal Judiciary

The American Bar Association (ABA) is a voluntary bar association of lawyers and law students, which is not specific to any jurisdiction in the United States. Founded in 1878, the ABA's most important stated activities are the setting of academ ...

rated Ginsburg as "well qualified", its highest rating for a prospective justice.

During her testimony before the

During her testimony before the Senate Judiciary Committee

The United States Senate Committee on the Judiciary, informally the Senate Judiciary Committee, is a standing committee of 22 U.S. senators whose role is to oversee the Department of Justice (DOJ), consider executive and judicial nominations, a ...

as part of the confirmation hearings, Ginsburg refused to answer questions about her view on the constitutionality of some issues such as the death penalty

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, is the state-sanctioned practice of deliberately killing a person as a punishment for an actual or supposed crime, usually following an authorized, rule-governed process to conclude that t ...

as it was an issue she might have to vote on if it came before the Court.

At the same time, Ginsburg did answer questions about some potentially controversial issues. For instance, she affirmed her belief in a constitutional right to privacy and explained at some length her personal judicial philosophy and thoughts regarding gender equality. Ginsburg was more forthright in discussing her views on topics about which she had previously written. The United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and pow ...

confirmed her by a 96–3 vote on August 3, 1993. She received her commission on August 5, 1993 and took her judicial oath on August 10, 1993.

Ginsburg's name was later invoked during the confirmation process of John Roberts

John Glover Roberts Jr. (born January 27, 1955) is an American lawyer and jurist who has served as the 17th chief justice of the United States since 2005. Roberts has authored the majority opinion in several landmark cases, including ''Nati ...

. Ginsburg was not the first nominee to avoid answering certain specific questions before Congress, and as a young attorney in 1981 Roberts had advised against Supreme Court nominees' giving specific responses. Nevertheless, some conservative commentators and senators invoked the phrase "Ginsburg precedent" to defend his demurrers. In a September 28, 2005, speech at Wake Forest University

Wake Forest University is a private research university in Winston-Salem, North Carolina. Founded in 1834, the university received its name from its original location in Wake Forest, north of Raleigh, North Carolina. The Reynolda Campus, the un ...

, Ginsburg said Roberts's refusal to answer questions during his Senate confirmation hearings on some cases was "unquestionably right".

Supreme Court tenure

Ginsburg characterized her performance on the Court as a cautious approach to adjudication. She argued in a speech shortly before her nomination to the Court that " asured motions seem to me right, in the main, for constitutional as well as common law adjudication. Doctrinal limbs too swiftly shaped, experience teaches, may prove unstable." Legal scholarCass Sunstein

Cass Robert Sunstein (born September 21, 1954) is an American legal scholar known for his studies of constitutional law, administrative law, environmental law, law and behavioral economics. He is also ''The New York Times'' best-selling author of ...

characterized Ginsburg as a "rational minimalist", a jurist who seeks to build cautiously on precedent rather than pushing the Constitution towards her own vision.

The retirement of Justice Sandra Day O'Connor in 2006 left Ginsburg as the only woman on the Court. Linda Greenhouse

Linda Joyce Greenhouse (born January 9, 1947) is an American legal journalist who is the Knight Distinguished Journalist in Residence and Joseph M. Goldstein Lecturer in Law at Yale Law School. She is a Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter who covered ...

of ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'' referred to the subsequent 2006–2007 term of the Court as "the time when Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg found her voice, and used it". The term also marked the first time in Ginsburg's history with the Court where she read multiple dissents from the bench, a tactic employed to signal more intense disagreement with the majority.

With the retirement of Justice

With the retirement of Justice John Paul Stevens

John Paul Stevens (April 20, 1920 – July 16, 2019) was an American lawyer and jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1975 to 2010. At the time of his retirement, he was the second-oldes ...

, Ginsburg became the senior member of what was sometimes referred to as the Court's "liberal wing". When the Court split 5–4 along ideological lines and the liberal justices were in the minority, Ginsburg often had the authority to assign authorship of the dissenting opinion

A dissenting opinion (or dissent) is an opinion in a legal case in certain legal systems written by one or more judges expressing disagreement with the majority opinion of the court which gives rise to its judgment.

Dissenting opinions are no ...

because of her seniority. Ginsburg was a proponent of the liberal dissenters speaking "with one voice" and, where practicable, presenting a unified approach to which all the dissenting justices can agree.

During Ginsburg's entire Supreme Court tenure from 1993 to 2020, she only hired one African-American clerk (Paul J. Watford

Paul Jeffrey Watford (born August 25, 1967) is an American lawyer serving as a United States circuit judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit since 2012. In February 2016, ''The New York Times'' identified Watford as a po ...

). During her 13 years on the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit

The United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit (in case citations, D.C. Cir.) is one of the thirteen United States Courts of Appeals. It has the smallest geographical jurisdiction of any of the U.S. federal appellate cou ...

, she never hired an African-American clerk, intern, or secretary. The lack of diversity was briefly an issue during her 1993 confirmation hearing. When this issue was raised by the Senate Judiciary Committee

The United States Senate Committee on the Judiciary, informally the Senate Judiciary Committee, is a standing committee of 22 U.S. senators whose role is to oversee the Department of Justice (DOJ), consider executive and judicial nominations, a ...

, Ginsburg stated that "If you confirm me for this job, my attractiveness to black candidates is going to improve." This issue received renewed attention after more than a hundred of her former legal clerks served as pallbearer

A pallbearer is one of several participants who help carry the casket at a funeral. They may wear white gloves in order to prevent damaging the casket and to show respect to the deceased person.

Some traditions distinguish between the roles of ...

s during her funeral

A funeral is a ceremony connected with the final disposition of a corpse, such as a burial or cremation, with the attendant observances. Funerary customs comprise the complex of beliefs and practices used by a culture to remember and respect th ...

.

Gender discrimination

Ginsburg authored the Court's opinion in '' United States v. Virginia'', , which struck down theVirginia Military Institute

la, Consilio et Animis (on seal)

, mottoeng = "In peace a glorious asset, In war a tower of strength""By courage and wisdom" (on seal)

, established =

, type = Public senior military college

, accreditation = SACS

, endowment = $696.8 mill ...

's (VMI) male-only admissions policy as violating the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. For Ginsburg, a state actor could not use gender to deny women equal protection; therefore VMI must allow women the opportunity to attend VMI with its unique educational methods. Ginsburg emphasized that the government must show an "exceedingly persuasive justification" to use a classification based on sex. VMI proposed a separate institute for women, but Ginsburg found this solution reminiscent of the effort by Texas decades earlier to preserve the University of Texas Law School for Whites by establishing a separate school for Blacks.

Ginsburg dissented in the Court's decision on '' Ledbetter v. Goodyear'', , in which plaintiff

Ginsburg dissented in the Court's decision on '' Ledbetter v. Goodyear'', , in which plaintiff Lilly Ledbetter

Lilly McDaniel Ledbetter (born April 14, 1938) is an American activist who was the plaintiff in the United States Supreme Court case '' Ledbetter v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co.'' regarding employment discrimination. Two years after the Supreme C ...

sued her employer, claiming pay discrimination based on her gender, in violation of TitleVII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 () is a landmark civil rights and United States labor law, labor law in the United States that outlaws discrimination based on Race (human categorization), race, Person of color, color, religion, sex, and nationa ...

. In a 5–4 decision, the majority interpreted the statute of limitations

A statute of limitations, known in civil law systems as a prescriptive period, is a law passed by a legislative body to set the maximum time after an event within which legal proceedings may be initiated. ("Time for commencing proceedings") In m ...

as starting to run at the time of every pay period, even if a woman did not know she was being paid less than her male colleague until later. Ginsburg found the result absurd, pointing out that women often do not know they are being paid less, and therefore it was unfair to expect them to act at the time of each paycheck. She also called attention to the reluctance women may have in male-dominated fields to making waves by filing lawsuits over small amounts, choosing instead to wait until the disparity accumulates. As part of her dissent, Ginsburg called on Congress to amend TitleVII to undo the Court's decision with legislation. Following the election of President Barack Obama

Barack Hussein Obama II ( ; born August 4, 1961) is an American politician who served as the 44th president of the United States from 2009 to 2017. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, Obama was the first Af ...

in 2008, the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act

The Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act of 2009 (, ) is a landmark federal statute in the United States that was the first bill signed into law by U.S. President Barack Obama on January 29, 2009. The act amends Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 ...

, making it easier for employees to win pay discrimination claims, became law. Ginsburg was credited with helping to inspire the law.

Abortion rights

Ginsburg discussed her views on abortion and gender equality in a 2009 ''New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid d ...

'' interview, in which she said, " e basic thing is that the government has no business making that choice for a woman." Although Ginsburg consistently supported abortion rights

Abortion-rights movements, also referred to as pro-choice movements, advocate for the right to have legal access to induced abortion services including elective abortion. They seek to represent and support women who wish to terminate their pre ...

and joined in the Court's opinion striking down Nebraska's partial-birth abortion

Intact dilation and extraction (D&X, IDX, or intact D&E) is a surgical procedure that removes an intact fetus from the uterus. The procedure is used both after miscarriages and for abortions in the second and third trimesters of pregnancy.

In U ...

law in ''Stenberg v. Carhart

''Stenberg v. Carhart'', 530 U.S. 914 (2000), was a landmark decision of the US Supreme Court dealing with a Nebraska law which made performing " partial-birth abortion" illegal, without regard for the health of the mother. Nebraska physicians wh ...

'', , on the 40th anniversary of the Court's ruling in ''Roe v. Wade

''Roe v. Wade'', 410 U.S. 113 (1973),. was a landmark decision of the U.S. Supreme Court in which the Court ruled that the Constitution of the United States conferred the right to have an abortion. The decision struck down many federal and st ...

'', , she criticized the decision in ''Roe'' as terminating a nascent democratic movement to liberalize abortion laws which might have built a more durable consensus in support of abortion rights.

Ginsburg was in the minority for ''Gonzales v. Carhart

''Gonzales v. Carhart'', 550 U.S. 124 (2007), was a landmark decision of the U.S. Supreme Court that upheld the Partial-Birth Abortion Ban Act of 2003. The case reached the high court after U.S. Attorney General, Alberto Gonzales, appealed a rul ...

'', , a 5–4 decision upholding restrictions on partial birth abortion. In her dissent, Ginsburg opposed the majority's decision to defer to legislative findings that the procedure was not safe for women. Ginsburg focused her ire on the way Congress reached its findings and with their veracity. Joining the majority for ''Whole Woman's Health v. Hellerstedt

''Whole Woman's Health v. Hellerstedt'', 579 U.S. 582 (2016), was a landmark decision of the US Supreme Court decided on June 27, 2016. The Court ruled 5–3 that Texas cannot place restrictions on the delivery of abortion services that create a ...

'', , a case which struck down parts of a 2013 Texas law

The law of Texas is derived from the ''Constitution of Texas'' and consists of several levels, including constitutional, statutory, and regulatory law, as well as case law and local laws and regulations.

Sources

The Constitution of Texas is t ...

regulating abortion providers, Ginsburg also authored a short concurring opinion which was even more critical of the legislation at issue. She asserted the legislation was not aimed at protecting women's health, as Texas had said, but rather to impede women's access to abortions.

Search and seizure

Although Ginsburg did not author the majority opinion, she was credited with influencing her colleagues on '' Safford Unified School District v. Redding'', , which held that a school went too far in ordering a 13-year-old female student to strip to her bra and underpants so female officials could search for drugs. In an interview published prior to the Court's decision, Ginsburg shared her view that some of her colleagues did not fully appreciate the effect of a strip search on a 13-year-old girl. As she said, "They have never been a 13-year-old girl." In an 8–1 decision, the Court agreed that the school's search violated the Fourth Amendment and allowed the student's lawsuit against the school to go forward. Only Ginsburg and Stevens would have allowed the student to sue individual school officials as well. In ''Herring v. United States

''Herring v. United States'', 555 U.S. 135 (2009), was a case decided by the Supreme Court of the United States on January 14, 2009. The court decided that the good-faith exception to the exclusionary rule applies when a police officer makes an a ...

'', , Ginsburg dissented from the Court's decision not to suppress evidence due to a police officer's failure to update a computer system. In contrast to Roberts's emphasis on suppression as a means to deter police misconduct, Ginsburg took a more robust view on the use of suppression as a remedy for a violation of a defendant's Fourth Amendment rights. Ginsburg viewed suppression as a way to prevent the government from profiting from mistakes, and therefore as a remedy to preserve judicial integrity and respect civil rights. She also rejected Roberts's assertion that suppression would not deter mistakes, contending making police pay a high price for mistakes would encourage them to take greater care.

International law

Ginsburg advocated the use of foreign law and norms to shape U.S. law in judicial opinions, a view rejected by some of her conservative colleagues. Ginsburg supported using foreign interpretations of law for persuasive value and possible wisdom, not as binding precedent. Ginsburg expressed the view that consulting international law is a well-ingrained tradition in American law, countingJohn Henry Wigmore

John Henry Wigmore (1863–1943) was an American lawyer and legal scholar known for his expertise in the law of evidence and for his influential scholarship. Wigmore taught law at Keio University in Tokyo (1889–1892) before becoming the first ...

and President John Adams

John Adams (October 30, 1735 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, attorney, diplomat, writer, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the second president of the United States from 1797 to 1801. Befor ...

as internationalists. Ginsburg's own reliance on international law dated back to her time as an attorney; in her first argument before the Court, ''Reed v. Reed'', 404 U.S. 71 (1971), she cited two German cases. In her concurring opinion in ''Grutter v. Bollinger

''Grutter v. Bollinger'', 539 U.S. 306 (2003), was a landmark case of the Supreme Court of the United States concerning affirmative action in student admissions. The Court held that a student admissions process that favors "underrepresented minor ...

'', 539 U.S. 306 (2003), a decision upholding Michigan Law School

The University of Michigan Law School (Michigan Law) is the law school of the University of Michigan, a public research university in Ann Arbor, Michigan. Founded in 1859, the school offers Master of Laws (LLM), Master of Comparative Law (MCL ...

's affirmative action admissions policy, Ginsburg noted there was accord between the notion that affirmative action admissions policies would have an end point and agrees with international treaties designed to combat racial and gender-based discrimination.

Voting rights and affirmative action

In 2013, Ginsburg dissented in '' Shelby County v. Holder'', in which the Court held unconstitutional the part of theVoting Rights Act of 1965

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 is a landmark piece of federal legislation in the United States that prohibits racial discrimination in voting. It was signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson during the height of the civil rights movement ...

requiring federal preclearance before changing voting practices. Ginsburg wrote, "Throwing out preclearance when it has worked and is continuing to work to stop discriminatory changes is like throwing away your umbrella in a rainstorm because you are not getting wet."

Besides ''Grutter'', Ginsburg wrote in favor of affirmative action in her dissent in '' Gratz v. Bollinger'' (2003), in which the Court ruled an affirmative action policy unconstitutional because it was not narrowly tailored to the state's interest in diversity. She argued that "government decisionmakers may properly distinguish between policies of exclusion and inclusion...Actions designed to burden groups long denied full citizenship stature are not sensibly ranked with measures taken to hasten the day when entrenched discrimination and its after effects have been extirpated."

Native Americans

In 1997, Ginsburg wrote the majority opinion in '' Strate v. A-1 Contractors'' against tribal jurisdiction over tribal-owned land in a reservation. The case involved a nonmember who caused a car crash in theMandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara Nation

The Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara Nation (MHA Nation), also known as the Three Affiliated Tribes (Mandan: ''Miiti Naamni''; Hidatsa: ''Awadi Aguraawi''; Arikara: ''ačitaanu' táWIt''), is a Native American Nation resulting from the alliance of th ...

. Ginsburg reasoned that the state right-of-way on which the crash occurred rendered the tribal-owned land equivalent to non-Indian land. She then considered the rule set in ''Montana v. United States

''Montana v. United States'', 450 U.S. 544 (1981), was a Supreme Court case that addressed two issues: (1) Whether the title of the Big Horn Riverbed rested with the United States, in trust for the Crow Nation or passed to the State of Montana up ...

'', which allows tribes to regulate the activities of nonmembers who have a relationship with the tribe. Ginsburg noted that the driver's employer did have a relationship with the tribe, but she reasoned that the tribe could not regulate their activities because the victim had no relationship to the tribe. Ginsburg concluded that although "those who drive carelessly on a public highway running through a reservation endanger all in the vicinity, and surely jeopardize the safety of tribal members", having a nonmember go before an "unfamiliar court" was "not crucial to the political integrity, the economic security, or the health or welfare of the Three Affiliated Tribes" (internal quotations and brackets omitted). The decision, by a unanimous Court, was generally criticized by scholars of Indian law, such as David Getches

David Harding Getches () was Dean (education), dean and Raphael J. Moses Professor of Natural Resources Law at the University of Colorado Law School in Boulder, Colorado. He taught and wrote on water law, public land law, environmental law, and ...

and Frank Pommersheim

Frank Pommersheim is an American professor, author, and poet specializing in the field of American Indian law. Pommersheim is serving on several tribal appellate courts and serves as the Chief Justice for the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribal Court ...

.

Later in 2005, Ginsburg cited the doctrine of discovery

The discovery doctrine, or doctrine of discovery, is a disputed interpretation of international law during the Age of Discovery, introduced into United States municipal law by the US Supreme Court Justice John Marshall in ''Johnson v. M'Intosh' ...

in the majority opinion of '' City of Sherrill v. Oneida Indian Nation of New York'' and concluded that the Oneida Indian Nation

The Oneida Indian Nation (OIN) or Oneida Nation is a federally recognized tribe of Oneida people in the United States. The tribe is headquartered in Verona, New York, where the tribe originated and held its historic territory long before Europea ...

could not revive its ancient sovereignty over its historic land. The discovery doctrine has been used to grant ownership of Native American lands to colonial governments. The Oneida had lived in towns, grew extensive crops, and maintained trade routes to the Gulf of Mexico. In her opinion for the Court, Ginsburg reasoned that the historic Oneida land had been "converted from wilderness" ever since it was dislodged from the Oneidas' possession. She also reasoned that "the longstanding, distinctly non-Indian character of the area and its inhabitants" and "the regulatory authority constantly exercised by New York State and its counties and towns" justified the ruling. Ginsburg also invoked, sua sponte

In law, ''sua sponte'' (Latin: "of his, her, its or their own accord") or ''suo motu'' ("on its own motion") describes an act of authority taken without formal prompting from another party. The term is usually applied to actions by a judge taken wi ...

, the doctrine of laches, reasoning that the Oneidas took a "long delay in seeking judicial relief". She also reasoned that the dispossession of the Oneidas' land was "ancient". Lower courts later relied on ''Sherrill'' as precedent to extinguish Native American land claims, notably in ''Cayuga Indian Nation of New York v. Pataki

''Cayuga Indian Nation of New York v. Pataki'', 413 F.3d 266 (2d Cir. 2005), is an important precedent in the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit for the litigation of aboriginal title in the United States. Applying the U.S. S ...

''.

Less than a year after ''Sherrill'', Ginsburg offered a starkly contrasting approach to Native American law. In December 2005, Ginsburg dissented in '' Wagnon v. Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation'', arguing that a state tax on fuel sold to Potawatomi

The Potawatomi , also spelled Pottawatomi and Pottawatomie (among many variations), are a Native American people of the western Great Lakes region, upper Mississippi River and Great Plains. They traditionally speak the Potawatomi language, a m ...

retailers would impermissibly nullify the Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation

Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation ( pot, Mshkodéniwek, formerly the Prairie Band of Potawatomi Indians) is a federally recognized tribe of Neshnabé (Potawatomi people), headquartered near Mayetta, Kansas.

History

The ''Mshkodésik'' ("People of t ...

's own tax authority. In 2008, when Ginsburg's precedent in ''Strate'' was used in '' Plains Commerce Bank v. Long Family Land & Cattle Co.'', she dissented in part and argued that the tribal court of the Cheyenne River Lakota Nation had jurisdiction over the case. In 2020, Ginsburg joined the ruling of ''McGirt v. Oklahoma

''McGirt v. Oklahoma'', 591 U.S. ___ (2020), was a landmark United States Supreme Court case which ruled that, as pertaining to the Major Crimes Act, much of the eastern portion of the state of Oklahoma remains as Native American lands of the pr ...

'', which affirmed Native American jurisdictions over reservations in much of Oklahoma.

Other notable majority opinions

In 1999, Ginsburg wrote the majority opinion in '' Olmstead v. L.C.,'' in which the Court ruled that mental illness is a form of disability covered under theAmericans with Disabilities Act of 1990

The Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 or ADA () is a civil rights law that prohibits discrimination based on disability. It affords similar protections against discrimination to Americans with disabilities as the Civil Rights Act of 19 ...

.

In 2000, Ginsburg wrote the majority opinion in '' Friends of the Earth, Inc. v. Laidlaw Environmental Services, Inc.'', in which the Court held that residents have standing to seek fines for an industrial polluter that affected their interests and that is able to continue doing so.

Decision not to retire under Obama

WhenJohn Paul Stevens

John Paul Stevens (April 20, 1920 – July 16, 2019) was an American lawyer and jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1975 to 2010. At the time of his retirement, he was the second-oldes ...

retired in 2010, Ginsburg became the oldest justice on the court at age 77. Despite rumors that she would retire because of advancing age, poor health, and the death of her husband, she denied she was planning to step down. In an interview in August 2010, Ginsburg said her work on the Court was helping her cope with the death of her husband. She also expressed a wish to emulate Justice Louis Brandeis

Louis Dembitz Brandeis (; November 13, 1856 – October 5, 1941) was an American lawyer and associate justice on the Supreme Court of the United States from 1916 to 1939.

Starting in 1890, he helped develop the "right to privacy" concept ...

's service of nearly 23years, which she achieved in April 2016.

Several times during the presidency of Barack Obama

Barack Obama's tenure as the 44th president of the United States began with his first inauguration on January 20, 2009, and ended on January 20, 2017. A Democrat from Illinois, Obama took office following a decisive victory over Republican n ...

, progressive attorneys and activists called for Ginsburg to retire so that Obama could appoint a like-minded successor, particularly while the Democratic Party Democratic Party most often refers to:

*Democratic Party (United States)

Democratic Party and similar terms may also refer to:

Active parties Africa

*Botswana Democratic Party

*Democratic Party of Equatorial Guinea

*Gabonese Democratic Party

*Demo ...

held control of the U.S. Senate. Ginsburg reaffirmed her wish to remain a justice as long as she was mentally sharp enough to perform her duties. In 2013, Obama invited her to the White House when it seemed likely that Democrats would lose control of the Senate, but she again refused to step down. She opined that Republicans would use the judicial filibuster to prevent Obama from appointing a jurist like herself. She stated that she had a new model to emulate in her former colleague, Justice John Paul Stevens, who retired at the age of 90 after nearly 35 years on the bench.Biskupic, JoanExclusive: Supreme Court's Ginsburg vows to resist pressure to retire

,

Reuters

Reuters ( ) is a news agency owned by Thomson Reuters Corporation. It employs around 2,500 journalists and 600 photojournalists in about 200 locations worldwide. Reuters is one of the largest news agencies in the world.

The agency was estab ...

, July 4, 2013.

Some believed that, in the lead-up to the 2016 U.S. presidential election, Ginsburg was waiting for candidate Hillary Clinton to beat candidate Donald Trump before retiring, because Clinton would nominate a more liberal successor for her than Obama would. After Trump's victory in 2016 and the election of a Republican Senate, she would have had to wait until the 2020 election for a Democrat to be president, but died in office in September 2020 at age 87.

Other activities

At his request, Ginsburg administered the

At his request, Ginsburg administered the oath of office

An oath of office is an oath or affirmation a person takes before assuming the duties of an office, usually a position in government or within a religious body, although such oaths are sometimes required of officers of other organizations. Such ...

to Vice President Al Gore

Albert Arnold Gore Jr. (born March 31, 1948) is an American politician, businessman, and environmentalist who served as the 45th vice president of the United States from 1993 to 2001 under President Bill Clinton. Gore was the Democratic Part ...

for a second term during the second inauguration of Bill Clinton

The second inauguration of Bill Clinton as president of the United States was held on Monday, January 20, 1997, at the West Front of the United States Capitol Building in Washington, D.C. This was the 53rd inauguration and marked the commencemen ...

on January 20, 1997. She was the third woman to administer an inaugural oath of office. Ginsburg is believed to have been the first Supreme Court justice to officiate at a same-sex wedding, performing the August 31, 2013, ceremony of Kennedy Center

The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts (formally known as the John F. Kennedy Memorial Center for the Performing Arts, and commonly referred to as the Kennedy Center) is the United States National Cultural Center, located on the Potom ...

president Michael Kaiser

Michael M. Kaiser (born October 27, 1953) is an American arts administrator who served as president of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts (2001–2014) in Washington, D.C.

Dubbed "the turnaround king" for his work at such arts i ...

and John Roberts, a government economist. Earlier that summer, the Court had bolstered same-sex marriage rights in two separate cases. Ginsburg believed the issue being settled led same-sex couples to ask her to officiate as there was no longer the fear of compromising rulings on the issue.

The Supreme Court bar formerly inscribed its certificates " in the year of our Lord", which some Orthodox Jews

Orthodox Judaism is the collective term for the traditionalist and theologically conservative branches of contemporary Judaism. Jewish theology, Theologically, it is chiefly defined by regarding the Torah, both Torah, Written and Oral Torah, Or ...

opposed, and asked Ginsburg to object to. She did so, and due to her objection, Supreme Court bar members have since been given other choices of how to inscribe the year on their certificates.

Despite their ideological differences, Ginsburg considered Antonin Scalia her closest colleague on the Court. The two justices often dined together and attended the opera. In addition to befriending modern composers, including Tobias Picker

Tobias Picker (born July 18, 1954) is an American composer, artistic director, and pianist, noted for his orchestral works ''Old and Lost Rivers'', ''Keys To The City'', and ''The Encantadas'', as well as his operas ''Emmeline'', ''Fantastic Mr. ...

, in her spare time, Ginsburg appeared in several operas in non-speaking supernumerary

Supernumerary means "exceeding the usual number".

Supernumerary may also refer to:

* Supernumerary actor, a performer in a film, television show, or stage production who has no role or purpose other than to appear in the background, more commonl ...

roles such as ''Die Fledermaus